HOW DO I START? |

LIMITED ENROLLMENT |

|

We ask that all beginners visit the CSJCC any Tuesday or Thursday to watch one practice before beginning. To get an idea of the martial art, please look below, at our Practice and section. Upon deciding to practice, you are invited to a first practice no charge.

What you need to know before practicing:

You must pay the dues to the CSJCC at the beginning of every month. This Dojo is non-profit, meaning fees go directly to the community center. None of our instructors are paid to teach kendo . We do, accept donations that support the website, new equipment for the dojo, traveling fees and events held by Shin Sou Fu Kan. How Does Ranking Work?Kendo practitioners do not wear any rank identifications. Ranks are based on a system from the Japanese chess game "Go."

There are a total of 14 ranks in kendo; 6"kyu"ranks (lower level) and 8 "dan"ranks (higher level). All ranks are attained through nationally sanctioned examinations conducted by a panel of instructors appointed by the AUSKF (All United States Kendo Federation), |

We have a limited 5 spot, open enrollment new-comers to kendo. The following months, are available for sign-up:

-January -Feb -April - May -June -October "Please note, this only apply's for people with no prior kendo experience. Kenshi, with formal training can start anytime." DOJO PRACTICE TIMES

TUES & THURS 6:30pm-8:00pm Contact: Michael Lindsay [email protected] (918) 495-1111 Charles Schusterman Jewish Community Center 2021 E 71ST ST, Tulsa, OK 74136 |

PRACTICE AND EQUIPMENT

| kendo_practice_routine_guidelines_with_kanji.pdf | |

| File Size: | 339 kb |

| File Type: | |

| kendo_beginners_equipment_guide_compressed.pdf | |

| File Size: | 609 kb |

| File Type: | |

Practice begins according to the schedule, and participants should always endeavor to make it to practice on time.

1. Tai-so (exercises) members undergo a series of dynamic stretches before commencing practice.

2. Ashi-sabaki (footwork) that uses the entire length of the dojo floor.

3. suburi (practice swing) an individual technique, that involves a number of attacks using the bokuto (wooden practice sword).

4. Rei-ho (etiquette). Kendo places a large emphasis on proper attitude in the dojo, and respect should be maintained throughout the practice.

5. Keiko (practice) involving the use of bogu (protective equipment) and shinai (bamboo sword). This practice is very loud, and physically demanding.

6. After keiko, students again perform the rei-ho to close practice. Senior students present will offer individual advice to every participant for personal reflection and improvement outside of class.

REMEMBER: THIS IS YOUR PRACTICE! You will only ever get back what you put in, so do your best every time!

Equipment can be purchased from the following recommended websites:

www.maruyamakendosupply.com

www.e-mudo.com

www.e-bogu.com

www.alljapanbudogu.com

www.tozando.com

www.budo-aoi.com

www.mazkiya.net

www.kendo-kids.com

1. Tai-so (exercises) members undergo a series of dynamic stretches before commencing practice.

2. Ashi-sabaki (footwork) that uses the entire length of the dojo floor.

3. suburi (practice swing) an individual technique, that involves a number of attacks using the bokuto (wooden practice sword).

4. Rei-ho (etiquette). Kendo places a large emphasis on proper attitude in the dojo, and respect should be maintained throughout the practice.

5. Keiko (practice) involving the use of bogu (protective equipment) and shinai (bamboo sword). This practice is very loud, and physically demanding.

6. After keiko, students again perform the rei-ho to close practice. Senior students present will offer individual advice to every participant for personal reflection and improvement outside of class.

REMEMBER: THIS IS YOUR PRACTICE! You will only ever get back what you put in, so do your best every time!

Equipment can be purchased from the following recommended websites:

www.maruyamakendosupply.com

www.e-mudo.com

www.e-bogu.com

www.alljapanbudogu.com

www.tozando.com

www.budo-aoi.com

www.mazkiya.net

www.kendo-kids.com

HISTORY OF KENDO

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF KENDO

The single-edged, straight-bladed sword was probably introduced into Japan from Sui (589–618) or early Tang (618–907) China. The cultivation of sword skills flourished during the Kamakura period (1192–1333) with the development of the distinctive Japanese curved blade. It was during the Sengoku period of incessant civil war (1467–1568) in which famous swordsmen began to systematize their battle tested skills into schools or traditions known as ryu.

TOKUGAWA PERIOD

With the commencement of the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), Japanese society was finally unified. Society was stratified into the four classes of samurai warriors, farmers, artisans and merchants (shi-no-ko-sho). Although a distinct minority, the samurai stood at the top of the system. Although class distinctions were not always black and white, the governmental decrees from the mid to late 1600s banning other classes from possessing or wearing weapons made martials arts such as swordsmanship, at least officially, the domain of the samurai.

The Tokugawa period was a time of peace. However, samurai of all the feudal domains spread throughout Japan were expected to maintain military preparedness at all times. Skilled practitioners from the many schools of swordsmanship (kenjutsu) that had evolved sought employment as instructors to samurai of a given clan or domain, and later in private free-for-all dojo in the big cities. Of all the martial arts that existed, kenjutsu was the most prevalent during the Tokugawa period.

TRAINING METHODOLOGY AND

DEVELOPMENT OF EQUIPMENT

Due to the lack of actual combat opportunity during the Tokugawa period, the moral and spiritual elements of kenjutsu drawing on Confucianism, Shinto, and Buddhist teachings (especially Zen) became increasingly prominent. Kenjutsu developed into a vehicle for training the mind and body. At first, kata formed the basis of training methodology. Two adepts would face each other with live or blunted blades, or wooden swords and perform choreographed forms. The attacks would, in theory, stop just short of making actual contact.

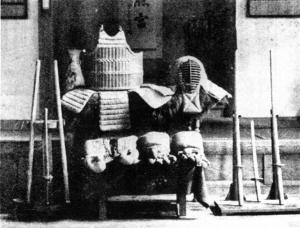

In the mid-18th century, Naganuma Shirozaemon Kunisato of the Jikishin Kage-ryu tradition developed protective equipment (bogu). This enabled swordsmen to make realistic attacks without holding back, and without the danger of maiming their opponent. This was revolutionary in that practitioners were no longer restricted to memorizing routines with predetermined outcomes. Soon after, Nakanishi Chuzo Tsugutake of the Itto-ryu developed the shinai (bamboo sword), which further stimulated the new training methodology. Before long other traditions adopted these innovations by introducing bogu and shinai into their curricula. Towards the end of the Tokugawa period a number of prominent dojo(training halls) specialising in kenjutsu utilising protective equipment for no-holds-barred sparring appeared in Edo (present day Tokyo). This was the golden era in the popularity of kenjutsu, and many of the fencing stars were not members of the samurai class.

MEIJI PERIOD KENJUTSU

Enthusiasm for traditional martial arts ended abruptly with the arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships to Japan’s shores in 1853. After centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan found itself completely out of its depth militarily in the face of Western incursion. Seclusion from the rest of the world had given the Japanese martial arts time to develop into fascinating martial antiques rich in ritualistic symbolism and spiritualism, but they were no match for the devastating firepower of Western nations. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and the dismantling of class distinctions, kenjutsu and other combat arts were all but discarded as outdated exercises with no practical use in the theater of modern warfare.

The single-edged, straight-bladed sword was probably introduced into Japan from Sui (589–618) or early Tang (618–907) China. The cultivation of sword skills flourished during the Kamakura period (1192–1333) with the development of the distinctive Japanese curved blade. It was during the Sengoku period of incessant civil war (1467–1568) in which famous swordsmen began to systematize their battle tested skills into schools or traditions known as ryu.

TOKUGAWA PERIOD

With the commencement of the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), Japanese society was finally unified. Society was stratified into the four classes of samurai warriors, farmers, artisans and merchants (shi-no-ko-sho). Although a distinct minority, the samurai stood at the top of the system. Although class distinctions were not always black and white, the governmental decrees from the mid to late 1600s banning other classes from possessing or wearing weapons made martials arts such as swordsmanship, at least officially, the domain of the samurai.

The Tokugawa period was a time of peace. However, samurai of all the feudal domains spread throughout Japan were expected to maintain military preparedness at all times. Skilled practitioners from the many schools of swordsmanship (kenjutsu) that had evolved sought employment as instructors to samurai of a given clan or domain, and later in private free-for-all dojo in the big cities. Of all the martial arts that existed, kenjutsu was the most prevalent during the Tokugawa period.

TRAINING METHODOLOGY AND

DEVELOPMENT OF EQUIPMENT

Due to the lack of actual combat opportunity during the Tokugawa period, the moral and spiritual elements of kenjutsu drawing on Confucianism, Shinto, and Buddhist teachings (especially Zen) became increasingly prominent. Kenjutsu developed into a vehicle for training the mind and body. At first, kata formed the basis of training methodology. Two adepts would face each other with live or blunted blades, or wooden swords and perform choreographed forms. The attacks would, in theory, stop just short of making actual contact.

In the mid-18th century, Naganuma Shirozaemon Kunisato of the Jikishin Kage-ryu tradition developed protective equipment (bogu). This enabled swordsmen to make realistic attacks without holding back, and without the danger of maiming their opponent. This was revolutionary in that practitioners were no longer restricted to memorizing routines with predetermined outcomes. Soon after, Nakanishi Chuzo Tsugutake of the Itto-ryu developed the shinai (bamboo sword), which further stimulated the new training methodology. Before long other traditions adopted these innovations by introducing bogu and shinai into their curricula. Towards the end of the Tokugawa period a number of prominent dojo(training halls) specialising in kenjutsu utilising protective equipment for no-holds-barred sparring appeared in Edo (present day Tokyo). This was the golden era in the popularity of kenjutsu, and many of the fencing stars were not members of the samurai class.

MEIJI PERIOD KENJUTSU

Enthusiasm for traditional martial arts ended abruptly with the arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships to Japan’s shores in 1853. After centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan found itself completely out of its depth militarily in the face of Western incursion. Seclusion from the rest of the world had given the Japanese martial arts time to develop into fascinating martial antiques rich in ritualistic symbolism and spiritualism, but they were no match for the devastating firepower of Western nations. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and the dismantling of class distinctions, kenjutsu and other combat arts were all but discarded as outdated exercises with no practical use in the theater of modern warfare.

THE REVIVAL OF SWORDSMANSHIP

Sakakibara Kenkichi, a renowned swordsman lamented this sudden fall from grace. He set about rekindling interest in traditional martial arts by instigating a series of public demonstration matches (gekiken kogyo) starring destitute swordsmen. Sakakibara held the first of these curious martial circuses in Tokyo for 10 days commencing April 11 1873. Any member of the public was welcome to view the spectacle as long as they paid the entrance fee. The first show was a raging success and many more followed keeping the exciting sword duels of a bygone era in public view as a form of entertainment much like professional Sumo is enjoyed in Japan today.

The stars of the shows eventually found employment as kenjutsu instructors in the newly formed police force in the 1880s. Kawaji Toshiyoshi, the commissioner of police and a former samurai, saw the advantages of introducing fencing into police training. He thought it would be useful to keep officers of the law fit and mentally sharp to execute their duties. This spelled the end of the shows, but the historical importance of gekiken kogyo is beyond doubt. In many ways it is thanks to this chapter in history that we still have kendo today.

KENJUTSU IN SCHOOLS

Although the police quickly rediscovered the worth of kenjutsu, its acceptance as an educational tool in schools took much longer. From the 1870s as Japan set on its path to modernize some government officials voiced their inhibitions about totally Westernising the education system. They sought to retain certain aspects of “Japanese-ness” in the physical education curriculum, for example, which had a focus western gymnastics at that time.

To investigate the pros and cons of teaching kenjutsu in schools, the Ministry of Education sponsored several official surveys. Findings of one survey in 1883 acknowledged that it could be beneficial in complementing the knowledge-oriented school system with its emphasis on spiritual development, but there were still concerns that it might not meet the physiological benefits expected from physical education in that it may mitigate balanced physical development, encourage violence, not to mention that repeatedly hitting each other over the head with bamboo swords could be dangerous. In addition, the training equipment needed was expensive. It was also thought to be somewhat unhygienic as equipment would have to be shared. It took several decades of lobbying and rejigging before kenjutsu was acknowledged as a useful form of physical education.

DAI NIHON BUTOKUKAI (GREATER JAPAN SOCIETY OF MARTIAL VIRTUE)

The move to introduce kenjutsu into schools was greatly aided by the formation of the Dai-Nihon Butokukai in 1895. The Butokukai was established in Kyoto under the authority of the Ministry of Education and endorsed by the Meiji Emperor. Its goals were to preserve and promote Japan’s traditional martial arts. It also sought to standardise teaching methodology and technical forms for national dissemination in the school system.

In 1899, the Butokukai constructed its Butokuden dojo in Kyoto. Here, in 1905, they established a division to train martial arts instructors. In 1911 the Butokukai formed and ran the Butoku Gakko (School of Martial Virtue) which became known as the Bujutsu Senmon Gakko (Bujutsu Specialist School) in 1912, and then the Budo Senmon Gakko in 1919 when the term “bu-jutsu” was officially replaced with “bu-do” to emphasize the martial “Way” or educational aspects of the martial arts. It was from this time that ken-jutsu became commonly known as ken-do. The Butokukai actively promoted kendo and other martial arts by creating a ranking system, training teachers, and holding special events and tournaments, and it became a driving force behind the government’s decision to make martial arts into elective courses in schools from 1911.

DEVELOPMENT OF KENDO KATA

In an attempt to unify many kenjutsu traditions and their techniques, the Butokukai developed a new set of kendo kata. In 1912, they unveiled the Dai Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata (Great Japan Imperial Kendo Kata). Numerous amendments were made to ten kata procedures thereafter. However, it essentially constituted what modern exponents still practice as the Nippon Kendo Kata.

PRE-WAR MILITARISM AND KENDO

With the rising influence of militarism in the 1930s, the government mandated that schools stress “patriotism and spiritual training”. To this end, kendo was made a compulsory subject. By 1942, physical education focused on kendo, kyudo, judo, naginata (for girls) and rifle practice. The government adapted kendo to make it more combat-realistic. For example, emphasis on making one sacrificial attack became idealized rather than technical dexterity which might facilitate in winning bouts. Matches became ippon-shobu, or the first to get a point was the winner, as opposed to the best of three. Shinai became shorter to resemble the length of real swords and grappling from close quarters was also encouraged.

Sakakibara Kenkichi, a renowned swordsman lamented this sudden fall from grace. He set about rekindling interest in traditional martial arts by instigating a series of public demonstration matches (gekiken kogyo) starring destitute swordsmen. Sakakibara held the first of these curious martial circuses in Tokyo for 10 days commencing April 11 1873. Any member of the public was welcome to view the spectacle as long as they paid the entrance fee. The first show was a raging success and many more followed keeping the exciting sword duels of a bygone era in public view as a form of entertainment much like professional Sumo is enjoyed in Japan today.

The stars of the shows eventually found employment as kenjutsu instructors in the newly formed police force in the 1880s. Kawaji Toshiyoshi, the commissioner of police and a former samurai, saw the advantages of introducing fencing into police training. He thought it would be useful to keep officers of the law fit and mentally sharp to execute their duties. This spelled the end of the shows, but the historical importance of gekiken kogyo is beyond doubt. In many ways it is thanks to this chapter in history that we still have kendo today.

KENJUTSU IN SCHOOLS

Although the police quickly rediscovered the worth of kenjutsu, its acceptance as an educational tool in schools took much longer. From the 1870s as Japan set on its path to modernize some government officials voiced their inhibitions about totally Westernising the education system. They sought to retain certain aspects of “Japanese-ness” in the physical education curriculum, for example, which had a focus western gymnastics at that time.

To investigate the pros and cons of teaching kenjutsu in schools, the Ministry of Education sponsored several official surveys. Findings of one survey in 1883 acknowledged that it could be beneficial in complementing the knowledge-oriented school system with its emphasis on spiritual development, but there were still concerns that it might not meet the physiological benefits expected from physical education in that it may mitigate balanced physical development, encourage violence, not to mention that repeatedly hitting each other over the head with bamboo swords could be dangerous. In addition, the training equipment needed was expensive. It was also thought to be somewhat unhygienic as equipment would have to be shared. It took several decades of lobbying and rejigging before kenjutsu was acknowledged as a useful form of physical education.

DAI NIHON BUTOKUKAI (GREATER JAPAN SOCIETY OF MARTIAL VIRTUE)

The move to introduce kenjutsu into schools was greatly aided by the formation of the Dai-Nihon Butokukai in 1895. The Butokukai was established in Kyoto under the authority of the Ministry of Education and endorsed by the Meiji Emperor. Its goals were to preserve and promote Japan’s traditional martial arts. It also sought to standardise teaching methodology and technical forms for national dissemination in the school system.

In 1899, the Butokukai constructed its Butokuden dojo in Kyoto. Here, in 1905, they established a division to train martial arts instructors. In 1911 the Butokukai formed and ran the Butoku Gakko (School of Martial Virtue) which became known as the Bujutsu Senmon Gakko (Bujutsu Specialist School) in 1912, and then the Budo Senmon Gakko in 1919 when the term “bu-jutsu” was officially replaced with “bu-do” to emphasize the martial “Way” or educational aspects of the martial arts. It was from this time that ken-jutsu became commonly known as ken-do. The Butokukai actively promoted kendo and other martial arts by creating a ranking system, training teachers, and holding special events and tournaments, and it became a driving force behind the government’s decision to make martial arts into elective courses in schools from 1911.

DEVELOPMENT OF KENDO KATA

In an attempt to unify many kenjutsu traditions and their techniques, the Butokukai developed a new set of kendo kata. In 1912, they unveiled the Dai Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata (Great Japan Imperial Kendo Kata). Numerous amendments were made to ten kata procedures thereafter. However, it essentially constituted what modern exponents still practice as the Nippon Kendo Kata.

PRE-WAR MILITARISM AND KENDO

With the rising influence of militarism in the 1930s, the government mandated that schools stress “patriotism and spiritual training”. To this end, kendo was made a compulsory subject. By 1942, physical education focused on kendo, kyudo, judo, naginata (for girls) and rifle practice. The government adapted kendo to make it more combat-realistic. For example, emphasis on making one sacrificial attack became idealized rather than technical dexterity which might facilitate in winning bouts. Matches became ippon-shobu, or the first to get a point was the winner, as opposed to the best of three. Shinai became shorter to resemble the length of real swords and grappling from close quarters was also encouraged.

Shinai Kyougi Match

Shinai Kyougi Match

POST-WAR DEMOCRATIZATION

After Japan’s defeat in WWII, GHQ banned all budo participation, but enthusiasts still practiced in secret. Because of its association with the katana, kendo was viewed by the occupation authorities with particular suspicion and disdain. In September 1949, Tokyo Collegiate Kendo Federation alumni formed the Tokyo Kendo Club and set about looking at ways to revive kendo as a “sport suitable for a post-war democratic society”. They formulated a plan for a new sport called shinai kyogi. This hybrid version of kendo stressed the sporting aspects while consciously removing any hint of militarism and combative applications that were prevalent before and during the war.

THE ALL JAPAN SHINAI KYOGI FEDERATION AND THE ALL JAPAN KENDO FEDERATION

The All Japan Shinai Kyogi Federation was inaugurated 1950. Its aim was to promote and refine the rules and methodology of this new sporting creation. In 1952, the authorities permitted shinai kyogi as an elective subject in middle and high schools. In the same year, the All Japan Kendo Federation was formed, and conventional kendo was once again permitted. It was, however, in a far less pugnacious style than a decade earlier. In 1957 shinai kyogi and kendo combined to become ‘gakko kendo’ (school kendo) at which point the All Japan Shinai Kyogi Federation was dissolved, and shinai kyogi was seen no more.

With the launch of the All Japan Kendo Federation, the first annual All Japan Kendo Championships were held in 1953. The All Japan Collegiate Kendo Federation was formed in the same year; the All Japan Company Kendo Federation in 1957. 1961 saw the foundation of the All Japan School Kendo Federation. The mid 1960s and 1970s saw a massive boom in kendo’s popularity. It became the most fashionable martial art in Japan with considerably more practitioners than judo, karate, or any other art.

INTERNATIONAL SPREAD OF KENDO

Japanese immigrants to the USA, Brazil, and Canada took kendo with them at the beginning of the twentieth century. As Japanese colonies, Taiwan and Korea also had a healthy number of kendo practitioners in the pre-war years. Kendo’s following in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Oceania, however, never really amounted to much until the 1970s. The European Kendo Association was established in 1968, and European championships started in 1969.

17 countries and regions formed the FIK at a meeting in Tokyo in 1970. Its aim was to cultivate goodwill through the international propagation of kendo (also iaido and jodo). The FIK is responsible for holding the World Kendo Championships every three years. It also holds international seminars, assists in developing federation infrastructure in kendo developing countries, and conducts information exchange. As of 2017, there are 57 affiliate nations.

Outside Japan with its 1.5 million practitioners, Korea has the largest kendo population estimated at around 400,000. It is referred to as kumdo there and considered by many as traditional Korean culture. Korea in particular, is eager for kendo to become an Olympic sport, but most affiliates of the International Kendo Federation (FIK) have been opposed to such ideas through the fear that it encourages a win-at-all costs mentality that would be detrimental to the true essence of the art as a vehicle for self-perfection.

KENDO: TRADITION VERSUS SPORTS

The issue of whether kendo is “traditional culture” or a “sport” fuels heated discussions in Japan, often without a suitable definition for either. Some practitioners emphasize competition, particularly at high school and university level. Mature practitioners usually come to believe that overt competitiveness is in discordance with the true way of kendo. They believe focusing solely on victory or defeat detracts from the more important goal of character development. It was with this in mind that the All Japan Kendo Federation created the official Concept of Kendo, and The Purpose of Practicing Kendo in 1975.

The Concept of Kendo

The concept of kendo is to discipline the human character through the application of the principles of the katana (sword).

The Purpose of Practicing Kendo

The purpose of practicing kendo is:

To mold the mind and body,

To cultivate a vigorous spirit,

And through correct and rigid training,

To strive for improvement in the art of kendo,

To hold in esteem human courtesy and honour,

To associate with others with sincerity,

And to forever pursue the cultivation of oneself.

This will make one be able:

To love his/her country and society,

To contribute to the development of culture

And to promote peace and prosperity among all peoples.

Kendo is a popular martial art in Japan, and the number of practitioners outside Japan is constantly increasing. Although it is esteemed in Japan as a noble example of the country’s traditional culture, refinements are continually made to its rules, concepts to facilitate kendo’s integration and acceptance as a socially useful and fulfilling activity for the times. Alexander Bennett’s Kendo: Culture of the Sword (University of California Press) gives a detailed analysis of kendo’s historical significance and evolution.

SOUCE: Kendo-World

By Alex Bennett

After Japan’s defeat in WWII, GHQ banned all budo participation, but enthusiasts still practiced in secret. Because of its association with the katana, kendo was viewed by the occupation authorities with particular suspicion and disdain. In September 1949, Tokyo Collegiate Kendo Federation alumni formed the Tokyo Kendo Club and set about looking at ways to revive kendo as a “sport suitable for a post-war democratic society”. They formulated a plan for a new sport called shinai kyogi. This hybrid version of kendo stressed the sporting aspects while consciously removing any hint of militarism and combative applications that were prevalent before and during the war.

THE ALL JAPAN SHINAI KYOGI FEDERATION AND THE ALL JAPAN KENDO FEDERATION

The All Japan Shinai Kyogi Federation was inaugurated 1950. Its aim was to promote and refine the rules and methodology of this new sporting creation. In 1952, the authorities permitted shinai kyogi as an elective subject in middle and high schools. In the same year, the All Japan Kendo Federation was formed, and conventional kendo was once again permitted. It was, however, in a far less pugnacious style than a decade earlier. In 1957 shinai kyogi and kendo combined to become ‘gakko kendo’ (school kendo) at which point the All Japan Shinai Kyogi Federation was dissolved, and shinai kyogi was seen no more.

With the launch of the All Japan Kendo Federation, the first annual All Japan Kendo Championships were held in 1953. The All Japan Collegiate Kendo Federation was formed in the same year; the All Japan Company Kendo Federation in 1957. 1961 saw the foundation of the All Japan School Kendo Federation. The mid 1960s and 1970s saw a massive boom in kendo’s popularity. It became the most fashionable martial art in Japan with considerably more practitioners than judo, karate, or any other art.

INTERNATIONAL SPREAD OF KENDO

Japanese immigrants to the USA, Brazil, and Canada took kendo with them at the beginning of the twentieth century. As Japanese colonies, Taiwan and Korea also had a healthy number of kendo practitioners in the pre-war years. Kendo’s following in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Oceania, however, never really amounted to much until the 1970s. The European Kendo Association was established in 1968, and European championships started in 1969.

17 countries and regions formed the FIK at a meeting in Tokyo in 1970. Its aim was to cultivate goodwill through the international propagation of kendo (also iaido and jodo). The FIK is responsible for holding the World Kendo Championships every three years. It also holds international seminars, assists in developing federation infrastructure in kendo developing countries, and conducts information exchange. As of 2017, there are 57 affiliate nations.

Outside Japan with its 1.5 million practitioners, Korea has the largest kendo population estimated at around 400,000. It is referred to as kumdo there and considered by many as traditional Korean culture. Korea in particular, is eager for kendo to become an Olympic sport, but most affiliates of the International Kendo Federation (FIK) have been opposed to such ideas through the fear that it encourages a win-at-all costs mentality that would be detrimental to the true essence of the art as a vehicle for self-perfection.

KENDO: TRADITION VERSUS SPORTS

The issue of whether kendo is “traditional culture” or a “sport” fuels heated discussions in Japan, often without a suitable definition for either. Some practitioners emphasize competition, particularly at high school and university level. Mature practitioners usually come to believe that overt competitiveness is in discordance with the true way of kendo. They believe focusing solely on victory or defeat detracts from the more important goal of character development. It was with this in mind that the All Japan Kendo Federation created the official Concept of Kendo, and The Purpose of Practicing Kendo in 1975.

The Concept of Kendo

The concept of kendo is to discipline the human character through the application of the principles of the katana (sword).

The Purpose of Practicing Kendo

The purpose of practicing kendo is:

To mold the mind and body,

To cultivate a vigorous spirit,

And through correct and rigid training,

To strive for improvement in the art of kendo,

To hold in esteem human courtesy and honour,

To associate with others with sincerity,

And to forever pursue the cultivation of oneself.

This will make one be able:

To love his/her country and society,

To contribute to the development of culture

And to promote peace and prosperity among all peoples.

Kendo is a popular martial art in Japan, and the number of practitioners outside Japan is constantly increasing. Although it is esteemed in Japan as a noble example of the country’s traditional culture, refinements are continually made to its rules, concepts to facilitate kendo’s integration and acceptance as a socially useful and fulfilling activity for the times. Alexander Bennett’s Kendo: Culture of the Sword (University of California Press) gives a detailed analysis of kendo’s historical significance and evolution.

SOUCE: Kendo-World

By Alex Bennett